Green Paper Means Go

The once-in-a-generation BBC Charter review has finally begun. Has the Government already decided how it will end?

Welcome to Whose Beeb?, a newsletter about the BBC Charter review and the future of public media. You can read more about the ideas behind Whose Beeb? on the About page.

In this first bumper issue:

How the Government’s consultation shuts the public out of Charter review

Ads on Auntie - a double death sentence for funding

What happened to Lisa Nandy’s radical vision for democratic reform?

Ministers past and present reveal the mucky politics of BBC policymaking

Whose Beeb, and why?

Did you know that the BBC Charter review is happening right now? Do you know what it is? …do you particularly care?

If you’re a BBC wonk or working in the media industries, your answer to some of these questions might be ‘yes’. But if you’re one of the 70 million other (normal) people in the UK, the launch of the official Government review of the BBC’s Royal Charter probably passed you by.

Don’t worry, it’s not your fault. Dull announcements about media policy reviews will never get the same public attention as failures in BBC news coverage, major political scandals or eternal arguments about the ‘value’ of the licence fee.

But the BBC’s Royal Charter is fundamental to how the BBC works. And though we’re told that the BBC “belongs to all of us”, in reality the British public are treated as bystanders in the once-in-a-generation Charter review debates that decide how ‘our BBC’ is run, governed and funded.

Whose Beeb? is my humble attempt to change that, offering an unashamedly pro-public media (though by no means pro-BBC) account of this critical debate about the future of the BBC and public media in the UK. At the heart of Whose Beeb? is a simple question - if the BBC is meant to be a public service, owned and funded by the public, then why doesn’t the public get a genuine democratic say on its future?

Here goes!

‘Our’ BBC, Your ‘Say’, Their Decision

The Department for Culture, Media and Sport published its BBC Green Paper on 16th December, just days before the Christmas holidays. This was not an ideal moment to digest a dense 80-page document on the Government’s plans for the future of the BBC.

But the timing is even more significant for the launch of the Government’s public consultation, inviting members of the public to respond to an online survey about the proposals in the Green Paper. Once the Christmas break had passed, the realistic window for public submissions to this 11-week consultation was more like an 8-week chance to fill out a 20-minute questionnaire.

And as surveys go, this one is a shocking mess. That’s me being polite.

We’re treated to a 32-question marathon on BBC reform, seemingly tailor-made to put off the average interested member of the public. Most questions are either vague to the point of meaninglessness, or so steeped in BBC boffinry they need deciphering into plain English.

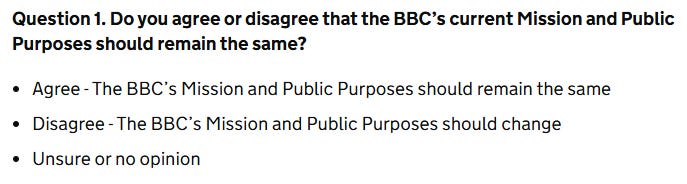

The consultation comes with an expectation that you have not only read the Green Paper in detail, but taken from it a crystal-clear picture of how the BBC works. Take Question 1, right out of the gate:

Answering this assumes you not only know what the five Public Purposes are, but also have a sense of what they mean in practice, and have a view on if the BBC has lived up to them - something which the Green Paper provides in only the thinnest overview, using mostly recycled statistics.

Even then, our thoughts on these Public Purposes - which are hugely significant to determining what the BBC is expected to provide for the public - are reduced to changing nothing, or changing something. How should you answer if you think three of the Purposes are effective, while the other two have failed to deliver public benefit? What if you want a brand new Purpose, or think the whole model of Public Purposes (only introduced in 2007) has failed to improve how the BBC works?

The majority of the survey is made up of these insultingly reductive tick-box questions. Many feature options that overlap. What is useful in discovering, for example, the proportion of people that think the BBC is “rarely” versus “almost never” accountable to the public, without letting them explain why and in what ways?

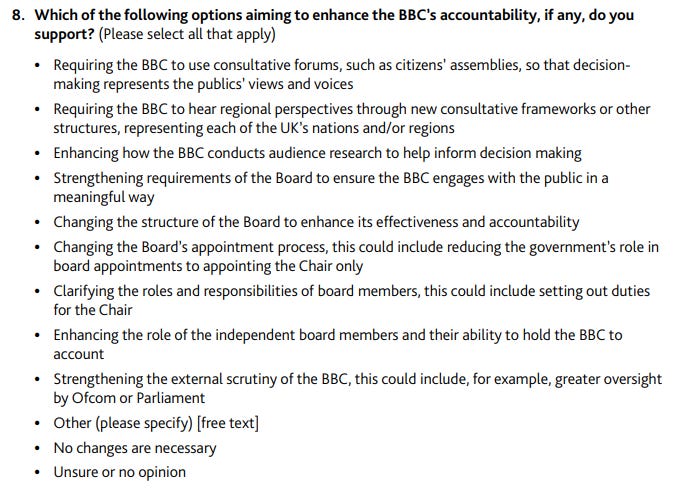

Others (like Question 8, below) provide sprawling shopping lists of idealistic reforms, each deserving of serious debate but given no specifics to understand how they work in practice. If you’ve ever tried to organise a friends’ night out over a WhatsApp poll, you’ll know the lumpy, inconclusive results these sorts of questions give.

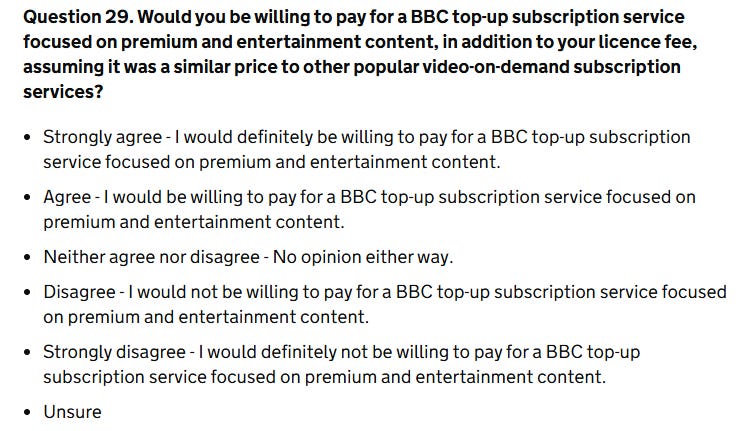

Worse still, some of the most important questions about the BBC’s future are heavily leading in favour of (what appear to be) the Government’s preferred BBC reforms. Question 29 takes the cake:

Note that you aren’t being asked whether the BBC should or should not introduce a top-up subscription service, or how it might impact the BBC’s mission to serve all audiences equally. The Government only wants to know if you would pay for it, as a kind of market research on a potential customer base.

The Government’s terms of reference suggest this survey will be the only opportunity for public participation in Charter review. Squashing our views into a handful of percentage figures won’t scratch the surface of fundamental questions about what kind of media system we want, and how the BBC fits into it, without a much deeper deliberative process - such as a national series of citizens’ assemblies.

Unless the Government immediately hits the brakes and radically revises its entire plan for Charter review, it’s difficult to see how the public are expected to feel a genuine stake in the Government’s vision for the BBC on to 2040 and beyond.

Ads on Auntie - a double death sentence for funding

In her foreword to the Green Paper, the Culture Secretary Lisa Nandy describes the BBC as “the beating heart of our nation”:

“I believe the BBC, alongside the NHS, is one of the two most important institutions in our country. While one is fundamental to the health of our people, the other is fundamental to the health of our democracy.”

I’m lucky enough to not yet need NHS cardiovascular advice. But I imagine it doesn’t say to keep your democracy’s metaphorical heart healthy by filling it with adverts for Uber Eats, Paddy Power and the latest AI-bloated smartphone.

What else explains the Government’s proposal to introduce adverts on some (if not all) of the BBC’s UK public services?

Allowing ads on the BBC would wreck a very precious feature of our public life and culture. For now, however, it’s enough to flag the obvious economic damage that even partial advertising on the BBC would create.

Bizarrely, the Green Paper recognises that the TV advertising market is in terminal decline. Throwing a new buyer the size of the BBC into this creaking sector would drive down the price of advertising, tanking revenues not just for an ad-funded BBC but for ITV, Channel 4, Sky and the wider commercial TV and radio sectors. As the Advertising Association’s Konrad Shek put it recently, “the BBC is likely to eat into a shrinking pie rather than expanding it”.

Non-linear advertising on the BBC’s digital services is unlikely to hold much value either. Search and online display advertising - dominated by Meta and Google - makes up three-quarters of the UK’s growing ad market, while spend on most ‘traditional’ kinds of advertising is consistently falling. BVoD advertising i.e. personalised digital ads on streaming platforms, accounted for just 3% of ad revenue in 2024. When the Green Paper claims that the BBC could “potentially generate significant revenue” from advertising, it is imagining a giant pot of cash that simply does not exist.

The Government’s vision for an ad-funded BBC doesn’t even aim to grow the BBC, let alone to help it plug the 38% shortfall in public funding since 2010. The Green Paper promises (against the spirit of an open-minded consultation) that the introduction of advertising on the BBC would “likely be accompanied by a reduction in the cost the licence fee”.

This would be a double death sentence to the BBC’s finances - less guaranteed public funding alongside a new dependence on a shaky broadcasting ad market. This is before you even consider how ads on Auntie would fundamentally change its character and audience appeal, and the knock-on effect for what kind of services and programmes it would choose to make to draw in advertisers at scale.

The BBC’s outgoing Director-General says ads on the BBC won’t work. The BBC’s competitors say ads won’t work. Media trade groups say ads won’t work. Advertisers say ads won’t work. The public… is unsure - panel research for the last Charter review in 2015-16 found (unsurprisingly) that audiences don’t like ads, but also really don’t like the licence fee.

That advertising and increasing the BBC’s commercial revenue are front-and-centre in this Green Paper feels like a concerted political choice. By completely ruling out any substantial reform to the TV licence fee - flippantly and baselessly described as “a tried and tested public funding model” - the Green Paper completely dodges the only essential debate on BBC funding: replacing the licence fee with something fairer, sustainable and progressive. That nettle will only get sharper the longer it’s left ungrasped.

Will the real Lisa Nandy please stand up

“To maintain the BBC as an institution, it must be accountable to those who fund it – the British people. Instead of tokenistic consultation with the people who pay for it, and backroom negotiations with the government, the BBC should move to a model of being owned and directed by licence fee holders – who can help decide the trade-offs that the BBC must make to secure its future.”

Wow that sounds great, who said that? Of course it was Lisa Nandy, now Culture Secretary and Charter-reviewer-in-chief, in her pitch for the Labour Party leadership in 2020.

Her encouragingly radical vision for BBC reform included “exploring mutualisation of parts of the corporation” - something Dan Hind, Tom Mills and I used to inspire our own model for a mutual BBC owned and controlled by the public as ‘members’.

So what happened? Why is there barely a whisper of BBC democratisation in the Green Paper?

Turning the BBC into a mutual still seemed on the table in January 2025, when The Times (£) reported that

“the radicalism of Nandy’s proposal will shock many who expected the government to retain the licence fee for another decade as the ‘least worst option’.”

It seems that Important People were frightened by the ‘Jeremy and Nigel problem’ pitched by an unnamed BBC executive, possibly quoted from a dark room while holding a torch under their chin:

“a divisive figure could win a popularity contest for a place on the board and use their position to attack the BBC from within.”

Putting aside what this reveals about BBC execs’ political affections. It suggests any official conversation on mutualisation started and stopped at the idea of public BBC Board elections - a significantly weaker vision of ‘democracy’ than the “genuine public representation and participation” Nandy v.2020 proposed.

Either you value the public’s views, or you don’t

Parliament’s modestly-attended Westminster Hall debate on Charter renewal featured the standard fare of MPs’ speeches on the BBC.

Sadly there wasn’t one instance of reminiscing about ‘programmes-I-done-watched-when-I-were-a-nipper’. We were however treated to GB News host Lee Anderson asking anyone to “find evidence of another broadcaster that has been riddled with as many scandals as the BBC”.

Two other, slightly more subtle moments in this debate stood out to me.

Conservative MP Nigel Huddleston bemoaned the “outrageous” proposal that “people claiming benefits [could be] given free TV licences while hard-working people footed the bill.”

(Ignore for a moment that Huddleston found it “disappointing” when in 2020 the BBC - and by extension ‘hard-working’ licence fee payers - stopped footing the bill for free TV licences for over-75s)

This apparent welfare robbery plot had been exposed in screeching front pages by the Telegraph and Mail back in December as "FREE BBC IF YOU LIVE ON BENEFITS ST”.

Responding for the Government, DCMS Minister Steph Peacock categorically ruled out expanding free TV licences for anyone.

Apparently it doesn’t matter that the Green Paper (supposedly an open book for public debate on BBC reforms) is considering “further targeted interventions, such as new concessions” - the Government has concluded the matter barely weeks into Charter review.

This demonstrates a classic dynamic in how politicians make decisions about the BBC: from front page, to parliament, and then straight into policy, with no public say whatsoever.

The second notable moment came from John Whittingdale, who had arranged the session and served as the very hands-on Culture Secretary during the last Charter review in 2015-16. The BBC we have today has JW’s fingerprints all over it.

In closing the debate, Whittingdale snuck in his own kind of reminiscing:

“It is important that as many people as possible respond to the consultation, although I suspect that the Minister and her officials may hope that we do not have a repeat of what happened last time, which was a 38 Degrees campaign generating 190,000 responses. The Department for Culture, Media and Sport had to hire a new building in order to count and read them all.”

It is extraordinary to have any politician hope for fewer public responses to a consultation, let alone one on something as significant as the future of the BBC.

It’s more extraordinary still coming from Whittingdale, who - despite claiming to have been “committed to reading and analysing” all of those responses - described the mass public engagement in the 2015-16 Charter review as “propaganda wars” and “a particular part of public opinion”.

DCMS under Whittingdale was also stung for allegedly not even opening 6,000 responses organised by the Radio Times, and convening an unminuted ‘advisory panel’ of commercial media execs to “feed into” the government’s reforms.

If this Government wants its BBC reforms to have any sort of public legitimacy, it would do very well to ignore the anti-democratic advice of John Whittingdale, and his special pleading for the office costs of a £1.6bn Government department.